Microscope Lab #2

|

Biology 1 Microscope Lab #2 |

|

Background Information

What Is a Microscope

In the most basic sense, a microscope is a tool that’s used to see objects that

are too small to be seen by the eye alone. There are many things happening in

the world around us and inside of us that we simply can’t see, although we know

that they happen. Blood cells move through the body carrying nutrients and

oxygen, but without a microscope, we can’t see those individual blood cells.

Because microscopes are so useful, they’ve become an essential tool in many

fields of science and have helped us understand how the world works. But how do

microscopes work, and are they all the same?

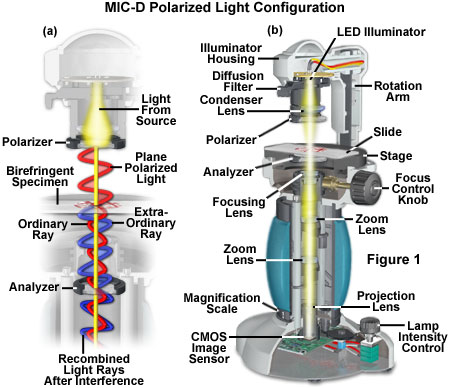

How Does a Microscope Work

The very first microscopes weren’t very effective, but they’re a good

illustration of how a microscope works. They were created by opticians who were

used to grinding glass into lenses for people who needed eyeglasses.

These eyeglass makers realized that if they put one lens at the bottom of a tube

and one at the top, they could use the power of both lenses to see tiny objects

more clearly. These original microscopes were the first examples of compound

microscopes, which are microscopes that use more than one lens to view objects.

An even more basic microscope is a single convex lens, which we call a

magnifying glass.

In a basic compound microscope, the lens at the bottom of the tube which is

closest to the object is the objective lens. This lens takes the light rays that

bounce off the object and spreads them apart through a convex lens so they

appear bigger. When they appear bigger, we can see them in greater detail than

we could without the aid of the lenses.

At the top of the compound microscope is another lens which is called the

eyepiece. This lens also magnifies the image coming from the objective lens to

give you a more detailed and clearer view of the subject.

While two lenses are necessary for a basic compound microscope to work, a light

source is also a key factor. Many microscopes today have their own light

sources, but a mirror behind and below the objective lens makes a great light

source that can be angled to hit the object precisely.

Detailed Steps of How a

Microscope Works

That’s the basic premise behind a microscope; it’s pretty simple with two lenses

and a light source. Let’s look at it one step at a time to further understand

what’s happening. We’ll use a basic compound microscope with two lenses to

continue the explanation.

Other Types of Microscopes

The basics of how a

compound microscope works are the same ones that are used in other microscopes.

Compound microscopes are still a very important and powerful tool, and they’re

used regularly, but there are some advances that have occurred in the more than

400 years since the first microscope, and we have some other options available.

These are a few of the more common microscopes available, but there are many

more to choose from. The field of microscopy has become very specialized,

allowing for detailed analysis in a variety of professions.

Part One: Making Temporary or Wet-Mount Slides

What is a wet-mount slide:

How is a wet-mount slide made:

When is a wet-mount slide used:

Temporary mount slides are often used to

observe live organisms or time-sensitive samples, such as

microscopic organisms in pond water.

Why is a wet-mount slide only temporary:

The water evaporates, so the slide can't be

stored for long periods of time.

In contrast, a prepared slide is

permanently mounted using a solidifying mounting medium.

How do you make a wet-mount slide:

place a small sample of your specimen on a clean slide

add a single drop of water (or other liquid-type stain) on top of the specimen

carefully lower a cover-slip onto the slide at an angle that will avoid producing air bubbles (usually a 45º angle will do this)

Materials Needed for Part One:

Procedure for Part One:

1. Find the smallest letter "e" in the newsprint like the one below, and using your scissors cut it out of the newspaper.

2. Using water, make a temporary or wet-mount slide of this letter "e". Use your tweezers to manipulate it so that it is in the "reading position" like the diagram below:

3. View the letter "e" under low power and medium power. Make your sketches of the letter "e" EXACTLY AS IT LOOKS AS YOU VIEW IT WITH THE MICROSCOPE. You can just draw this with a pencil. You do not need to make a colored sketch.

4. Discard this wet-mount slide in the appropriate trash receptacle.

Part Two: Making Wet-Mount Slides with Stain

Why use stains:

Stains are used when viewing cells under a microscope to

enhance their visibility by creating contrast between different cell components,

allowing for better observation of cell structures and morphology, as most cells

are naturally transparent and difficult to see without staining; essentially,

stains "color" specific parts of a cell, making them easier to distinguish from

their surroundings.

The biological stain that we use is called crystal-violet. It is made by dissolving the dry powder in a sample of water. Since this stain affects all biological items you should be careful so as not to get any of this stain on your hands or clothing. This stain is "semi-permanent" on you skin (usually comes off after a number of hand washings), but will be permanent if it gets on your clothing.

Materials Needed for Part Two:

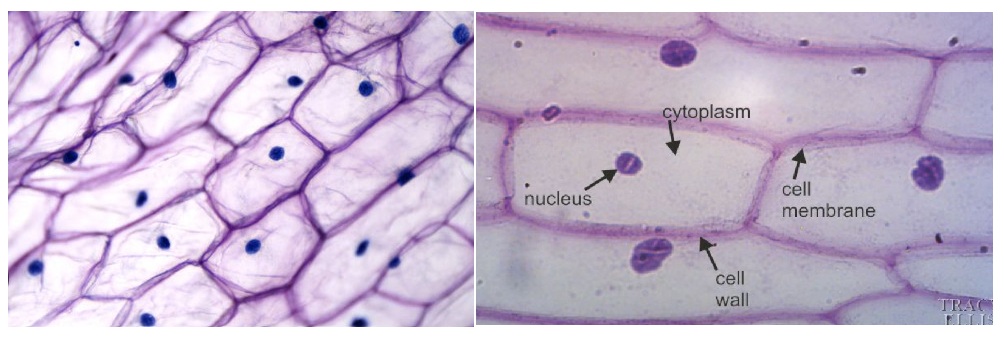

Procedure: Onion Skin Observation

1. Remove some onion skin from the onion as discussed earlier in class, and place it on the clean glass slide. Be sure to smooth it out as best as possible so there are few to no wrinkles in it.

2. Place a drop of crystal-violet stain on top of the onion skin and cover with a cover slip being careful to avoid air bubbles.

3. View the onion skin slide under low and medium power and make sketches of what you see. Use colored pencils to make your sketches colorful. When you make your sketches, use a regular pencil to draw the outline of the specimen and then use colored pencils to fill in the colors; this will make for a better looking sketch and will also help you define the cell membranes for each sketches.

4. This is what stained onion skin should look like under the microscope:

5. Discard the onion skin slide you made into the designated trash receptacle.

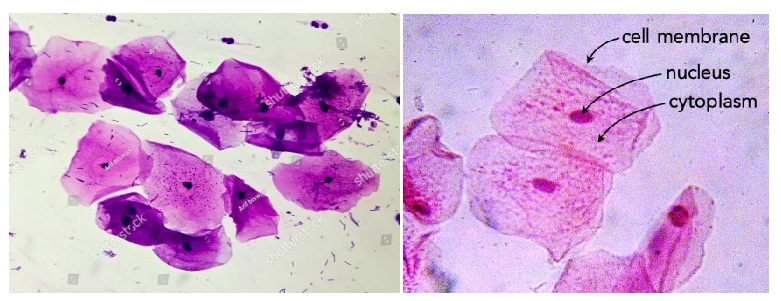

Procedure: Human Cheek Cell Observation

1. With the toothpick provided, gently scrape the inside of your cheek to get some cells on the end of the toothpick.

2. You do not have to scrape very hard, and more than likely you will not even see anything on the end of the toothpick.

3. Swab the end of the toothpick that contains your cheek cells onto a clean slide. Again, it may not look like much other than a smudge, but cells are there.

4. With the pipette, add a drop of crystal-violet stain to the cells and add a cover-slip on top of the cells that you just stained.

5. The stain will also bring into view the nucleus of the cell. The nucleus will appear as the round, darker, middle portion of the cell. It is these types of cells that the Forensic Scientists (CSI dudes) collect and test for DNA when they take a cotton Q-tip and swab the inside of a suspect's mouth. Each cell they collect will contain thousands of DNA molecules which can be used to positively identify an individual. This is what these cells might look like:

6. Use your microscope to view these cells under both low and high power. Make sketches of what you see. Use colored pencils to enhance your diagrams. When you make your sketches, use a regular pencil to draw the outline of the specimen and then use colored pencils to fill in the colors; this will make for a better looking sketch and will also help you define the cell membranes for each sketches.

7. Discard the cheek cell slide you made into the designated trash receptacle.

8. Complete the Microscope Lab #2 Review (Jupiter Ed) assignment.