Tarantula & Scorpion WebQuest

Scorpions

Scorpions

are eight-legged

arthropods.

A member of the

Arachnida

class and belonging to the order Scorpiones, there are about 2000 species of

scorpions. They are found widely distributed south of

49°

N, except

New

Zealand and

Antarctica.

The northern-most part of the world where scorpions live in the wild is

Sheerness

on the

Isle

of Sheppey in the

UK,

where a small colony of

Euscorpius

flavicaudis has been resident since the 1860s.

The

cuticle makes a tough armor around the body. In some places it is covered with

hairs that act like balance organs. An outer layer that makes them fluorescent

green under

ultraviolet

light is called the hyaline layer. Newly molted scorpions do not glow until

after their cuticle has hardened. The fluoresent hyaline layer can be intact in

fossil rocks that are hundreds of millions of years old.

The

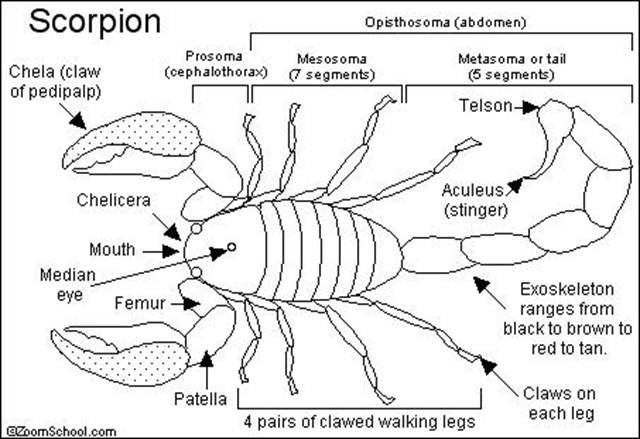

body of a scorpion is divided into two segments: the

cephalothorax

(also called the prosoma) and the

abdomen/opisthosoma.

The abdomen consists of the

mesosoma

and the metasoma.

The

cephalothorax, also called prosoma, is the scorpion's “head”, comprising the

carapace,

eyes,

chelicerae

(mouth parts),

pedipalps

(claw) and four

pairs of

walking

legs.

The

mesosoma, the abdomen's front half, is made up of six segments. The first

segment contains the

sexual

organs as well as a pair of vestigial and modified appendages forming a

structure called the genital operculum. The second segment bears a pair of

featherlike

sensory

organs known as the pectines; the final four segments each contain a pair of

book

lungs. The mesosoma is

armored

with

chitinous

plates, known as

tergites

on the upper surface and

sternites

on the lower surface.

The

metasoma, the scorpion's

tail,

comprising six segments (the first tail segment looks like a last mesosoman

segment), the last containing the scorpion's

anus

and bearing the

telson

(the

sting).

The telson, in turn, consists of the

vesicle,

which holds a pair of

venom

glands and the hypodermic aculeus, the venom-injecting barb.

On rare occasions, scorpions can be born with two metasomata (tails). Two-tailed scorpions are not a different species, but rather a genetic abnormality.

Most

scorpions reproduce sexually and most species have male and female individuals.

While the majority of scorpion species reproduce sexually, some, such as

Hottentotta

hottentotta,

Liocheles

australasiae,

Tityus

columbianus,

Tityus

metuendus,

Tityus

serrulatus,

Tityus

stigmurus,

Tityus

trivittatus, and

Tityus

urugayensis, all reproduce through

parthenogenesis, a process

in which unfertilized eggs develop into living

embryos.

Parthenogenic reproduction starts following the scorpion's final moult to

maturity and continues thereafter. Sexual reproduction is accomplished by the

transfer of a

spermatophore

from the

male to

the

female;

scorpions possess a complex

courtship

and

mating

ritual to effect this transfer. Mating starts with the

male

and

female

locating and identifying each other using a mixture of

pheromones

and

vibrational

communication; once they have satisfied each other that they are of opposite sex

and of the correct species, mating can commence.

The

courtship starts with the male grasping the female’s pedipalps with his own;

the pair then performs a "dance" called the "promenade à deux".

In reality this is the male leading the female around searching for a suitable

place to deposit his

spermatophore.

The courtship ritual can involve several other behaviours such as

juddering

and a cheliceral kiss, in which the male's chelicerae--clawlike

mouthparts--grasp the female's in a smaller more intimate version of the male's

grasping the female's pedipalps and in some cases injecting a small amount of

his venom into her pedipalp or on the edge of her cephalothorax, probably as a

means of pacifying the female.

When

he has identified a suitable location, he deposits the spermatophore and then

guides the female over it. This allows the spermatophore to enter her

genital

opercula, which triggers release of the sperm, thus fertilizing the female.

The mating process can take from 1 to 25+ hours and depends on the ability of

the male to find a suitable place to deposit his spermatophore. If mating goes

on for too long, the female may eventually break off the process.

Once

the mating is complete, the male and female quickly separate. The male will

generally retreat quickly, most likely to avoid being cannibalized by the

female, although sexual

cannibalism

is infrequent with scorpions.

Compsobuthus

werneri female with young

Unlike the majority of Arachnida species, scorpions are viviparous. The young are born one by one, and the brood is carried about on its mother's back until the young have undergone at least one moult. Before the first moult, scorplings cannot survive naturally without the mother, depending on her for protection and to regulate their moisture levels. Especially in species which display more advanced sociability (e.g Pandinus spp.), the young/mother association can continue for an extended period of time. The size of the litter depends on the species and environmental factors, and can range from two to over a hundred scorplings.

The

young generally resemble their parents. Growth is accomplished by periodic

shedding of the exoskeleton (ecdysis).

A scorpion's developmental progress is measured in

instars

(how many moults it has undergone). Scorpions typically require between five and

seven moults to reach maturity. Moulting is effected by means of a split in the

old

exoskeleton

which takes place just below the edge of the carapace (at the front of the

prosoma). The scorpion then emerges from this split; the pedipalps and legs are

first removed from the old exoskeleton, followed eventually by the

metasoma.

When it emerges, the scorpion’s new

exoskeleton

is soft, making the scorpion highly vulnerable to attack. The scorpion must

constantly stretch while the new exoskeleton hardens to ensure that it can move

when the hardening is complete. The process of hardening is called

sclerotization.

The new exoskeleton does not fluoresce; as

sclerotization

occurs, the fluorescence gradually returns.

Scorpions

have quite variable lifespans and the actual lifespan of most species is not

known. The age range appears to be approximately 4-25 years (25 years being the

maximum reported life span in the species H. arizonensis).Lifespan of Hadogenes

species in wild is estimated to 25-30 years.

Scorpions

prefer to live in areas where the temperatures range from 20°C to 37°C (68°F

to 99°F), but may survive from freezing temperatures to the desert heat.

Scorpions

of genus

Scorpiops

living in hight Asian mounties,Bothriuridae scorpions from Patagonia and smal

Euscorpius

scorpions from middle Europe in Winter survives temperatures about -25°C.

They are nocturnal and fossorial, finding shelter during the day in the relative cool of underground holes or undersides of rocks and coming out at night to hunt and feed. Scorpions exhibit photophobic behavior, primarily to evade destruction by their predators such as birds, centipedes, lizards, mice, possums, and rats.

Scorpions

are opportunistic predators of small arthropods and insects. They use their

chela (pincers) to catch the prey initially. Depending on the toxicity of their

venom and size of their claws, they will then either crush the prey or inject it

with

neurotoxic

venom. This will kill or paralyze the prey so the scorpion can eat it. Scorpions

have a relatively unique style of eating using

chelicerae,

small claw-like structures that protrude from the mouth that are found only in a

handful of invertebrates, including

spiders

and

vinegaroons.

The chelicerae, which are very sharp, are used to pull small amounts of food off

the prey item for digestion. Scorpions can only digest food in a liquid form;

any solid matter (fur,

exoskeleton,

etc) is disposed of by the scorpion.

Venom

All

scorpion species possess

venom.

In general, scorpion venom is described as

neurotoxic

in nature. One exception to this however is

Hemiscorpius

lepturus which possesses

cytotoxic

venom. The neurotoxins consist of a variety of small

proteins

as well as sodium and potassium

cations,

which serve to interfere with neurotransmission in the victim which causes

paralysis without damage to the tissues. Scorpions use

their venom to kill or paralyze their prey so that it can be eaten; in general

it is fast acting, allowing for effective prey capture. The effects of the sting

can be severe.

Scorpion

venoms are optimized for action upon other

arthropods

and therefore most scorpions are relatively harmless to

humans;

stings produce only local effects (such as pain, numbness or swelling). A few

scorpion species, however, mostly in the family

Buthidae,

can be dangerous to humans. Among the most dangerous are

Leiurus

quinquestriatus, otherwise dubiously known as the deathstalker, which has

the most potent venom in the family, and members of the genera

Parabuthus,

Tityus,

Centruroides,

and especially

Androctonus,

which also have powerful venom. The scorpion which is responsible for the most

human deaths is

Androctonus

australis, or the yellow fat-tailed scorpion of

North

Africa. The toxicity of A. australis's venom is roughly half that of L.

quinquestriatus, but despite the common misconception A. australis does not

inject noticeably more venom into its prey. The higher death count is simply due

to its being found more commonly, especially near humans. Human deaths normally

occur in the young, elderly, or infirm; scorpions are generally unable to

deliver enough venom to kill healthy adults. Some people, however, may be

allergic

to the venom of some species. Depending on the severity of the allergy, the

scorpion's sting may cause

anaphylaxis

and death. A primary symptom of a scorpion sting is numbing at the injection

site, sometimes lasting for several days. Scorpions are generally harmless and

timid, and only voluntarily use their sting for killing prey, defending

themselves or in territorial disputes with other scorpions. Generally, they will

run from danger or remain still.

It

should be noted that the family Buthidae, while containing perhaps the highest

number of dangerous species, also contains many species that are not thought to

be medically significant.

Scorpions

are able to regulate how much venom is injected with each sting using striated

muscles in the stinger, the usual amount being between 0.1 and 0.6 mg. There is

also evidence to suggest that scorpions restrict the use of their venom using it

only to subdue large prey, or prey that struggles. It has been found that

scorpions have two types of venom: a translucent, weaker venom designed to stun

only, and an opaque, more potent venom designed to kill heavier threats. This is

likely because it is expensive in terms of energy for a scorpion to produce

venom, and because it may take several days for a scorpion to replenish its

venom supply once it has been exhausted.

There

is currently no equivalent of the

Schmidt

Sting Pain Index because nobody has yet classified the levels of pain

inflicted by different scorpion stings. This is probably because of the risk

involved with some species, such as Androctonus australis or Leiurus

quinquestriatus. However, envenomation by a mildly venomous species like

Pandinus

imperator is similar to a bee sting in terms of the pain and swelling that

results. A sting on the thumb from a relatively non-dangerous scorpion often

feels like the victim has accidentally struck their

thumb

with a hammer whilst driving in a nail. A sting on the thumb from a truly

dangerous scorpion can feel much worse, as though the victim had hammered a nail

right through their thumb. It should be noted that the physical effects of a

sting from a medically significant scorpion are not limited to the pain

inflicted: there can be

bradycardia,

tachycardia

or in severe cases

pulmonary

edema.

The

stings of North American scorpions are rarely serious and usually result in

pain, minimal swelling, tenderness, and warmth at the sting site. However, the

Arizona bark scorpion (Centruroides

exilicauda or sculpturatus), which is found in Arizona and New Mexico and on

the California side of the Colorado River, has a much more toxic sting. The

sting is painful, sometimes causing numbness or tingling in the area around the

sting. Serious symptoms are more common in children and include abnormal head,

eye, and neck movements; increased saliva production; sweating; and

restlessness. Some people develop severe involuntary twitching and jerking of

muscles. Breathing difficulties may occur. The stings of most North American

scorpions require no special treatment. Placing an ice cube on the wound reduces

pain, as does an ointment containing a combination of an antihistamine, an

analgesic, and a corticosteroid. Centruroides stings that result in serious

symptoms may require the use of sedatives, such as midazolam, given

intravenously. Centruroides antivenom rapidly relieves symptoms, but it may

cause a serious allergic reaction or serum sickness. The antivenom is available

only in

Professor

Moshe

Gueron was the first to investigate the Cardiovascular Manifestations Affect

of Severe Scorpion Sting. Thousands

of stung patients were reviewed. Thirty-four patients with severe scorpion sting

were reviewed and pertinent data related to the cardiovascular system such as

hypertension, peripheral vascular collapse, congestive heart failure or

pulmonary edema were analyzed. The electrocardiograms of 28 patients were

reviewed; 14 patients showed "early myocardial infarction-like"

pattern. The urinary catecholamine metabolites were investigated in 12 patients

with scorpion sting. Vanylmandelic acid was elevated in seven patients and the

total free epinephrine and norepinephrine in eight. Six of these 12 patients

displayed the electrocardiographic "myocardial infarction-like"

pattern. Nine patients died and the pathologic lesions of the myocardium were

reviewed in seven. Also, Gueron reported five cases of Severe Myocardial damage

and heart failure in Scorpion sting from

Beer-Sheba,

Israel. He

described hypertension, pulmonary oedema with hypertension, hypotension,

pulmonary oedema with hypotension and rhythm disturbances as five different

syndromes that may dominate the clinical picture in scorpion sting victim. He

suggested that all patients with cardiac symptoms should be admitted to an

intensive cardiac unit. A few years later, at 1990, he was reported poor

contractility with low ejection fraction, decreased systolic left ventricular

performance, lowered fractional percentage shortening observed in

echocardiographic and radionuclide angiographic study. Gueron was questioned

regarding the value of giving antivenom, and he replied that although is freely

available, all cases of scorpion sting are treated without it, and there had not

been a single fatality in 1989.

Scorpions

have been found in many

fossil

records, including coal deposits from the

Carboniferous

Period and in marine

Silurian

deposits. They are thought to have existed in some form since about 425–450

million years ago. They are believed to have an oceanic origin, with gills and a

claw-like appendage that enabled them to hold onto rocky shores or

seaweed.

The

eurypterids,

marine

creatures which lived during the

Paleozoic

era, share several physical traits with scorpions and are closely related to

them. Various species of Eurypterida could grow to be anywhere from 10 cm (4 in)

to 3 m (9.75 ft) in length. However, they exhibit

anatomical

differences marking them off as a group distinct from their Carboniferous and

recent descendants. Despite this, some refer to them as "sea

scorpions." Their legs are thought to have been short, thick, tapering and

to have ended in a single strong claw; it appears that they were well-adapted

for maintaining a secure hold upon rocks or seaweed against the wash of waves,

like the legs of shore-crab.

Hadrurus spadix - Caraboctonidae, Hadrurinae

Scorpions

are almost universally distributed south of 49° N, and their geographical

distribution shows in many particulars a close and interesting correspondence

with that of the

mammals,

including their entire absence from

New

Zealand. The facts of their distribution are in keeping with the hypothesis

that the order originated in the

northern

hemisphere and migrated southwards into the southern continent at various

epochs, their absence from the countries to the north of the above-mentioned

latitudes being due, no doubt, to the comparatively recent

glaciation

of those areas. When they reached

Africa,

Madagascar

was part of that continent; but their arrival in

Australia

was subsequent to the separation of

In the

Five

colonies of scorpions (Euscorpius

flavicaudis) have established themselves in southern

England

having probably arrived with imported fruit from

Africa,

but the number of colonies could be lower now because of the destruction of

their habitats. This scorpion species is small and completely harmless to

humans.

Suicide

misconception

The

belief that scorpions commit suicide by stinging themselves to death when

surrounded by

fire

is of considerable antiquity and is often prevalent where these animals exist.

It is nevertheless untrue since the venom has no effect on the scorpion itself,

nor on any member of the same species (unless the venom is injected directly

into the scorpion's nerve ganglion—quite an unlikely event outside of the

laboratory). The misconception may derive from the fact that scorpions are

poikilotherms (cold-blooded):

when exposed to intense heat their metabolic processes malfunction. This causes

the scorpion to spasm wildly and this spasming may appear as if the scorpion is

stinging itself. It is also untrue that

alcohol

will cause scorpions to sting themselves to death.

A scorpion

under a

blacklight.

In normal lighting this scorpion appears black.

Scorpions

are also known to glow when exposed to certain wavelengths of

ultraviolet

light such as that produced by a

blacklight.

Tarantula

is the common name for a group of "hairy" and often very large

spiders

belonging to the

familyTheraphosidae,

of which approximately 900 species have been identified. Tarantulas hunt prey in

both trees and on the ground. All tarantulas can emit silk, whether they be

arboreal or terrestrial species. Arboreal species will typically reside in a

silken "tube web", and terrestrial species will line their burrows or

lairs with web to catch wandering prey. They mainly eat insects and other

arthropods, using ambush as their primary method. The biggest tarantulas can

kill animals as large as lizards, mice, or birds. Most tarantulas are harmless

to humans, and some species are popular in the exotic pet trade while others are

eaten as food. These spiders are found in tropical and desert regions around the

world.

The

name tarantula comes from the town of

Taranto

in Southern

Italy

and was originally used for an unrelated species of either European

wolf

spider (See

Lycosa

tarantula for more information about this spider the appearance of which

resembles that of that tarantula family) or the

Mediterranean

black widow (the effects of whose bite more closely resemble that described

in Taranto). In

There

are other species also referred to as tarantulas outside this family; the

evolution of the name Tarantula is discussed

below.

This article primarily concerns the Theraphosids.

Like all arthropods, the tarantula is an invertebrate that

relies on an exoskeleton for muscular support. A tarantula’s body consists of

two main parts, the

prosoma or the

cephalothorax (the former is most often used because there is no analogous

"head") and the abdomen or

opisthosoma. The prosoma

and opisthosoma are connected by the

pedicle or what is often

called the pregenital somite. This waist-like connecting piece is actually part

of the prosoma and allows the opisthosoma to move in a wide range of motion

relative to that of the prosom.

Depending

on the species, the body length of tarantulas range from 2.5 - 10 cm (1-4

inches), with 8-30 cm (3 to 12 inch) leg spans (their size when including their

legs). Legspan is determined by measuring from the tip of the back leg to the

tip of the front leg on the same side, although some people measure from the tip

of the first leg to the tip of the fourth leg on the other side. The largest

species of tarantulas can weigh over 9 grams (0.3 ounces). One candidate for the

title of the largest of all species, the

Theraphosa

blondi (goliath birdeater) from

Theraphosa

apophysis (the pinkfoot goliath) was described 187 years after the Goliath

birdeater; therefore its characteristics are not as well attested. However,

legspans of up to 33 cm (13 inches) have been reported for that species. T.

blondi is generally thought to be the heaviest tarantula, and T. apophysis the

largest legspan. Two other species,

Lasiodora

parahybana and

Lasiodora

klugi, (the Brazilian salmon birdeater) gets very large and rivals the size

of both Theraphosa blondi and Theraphosa apophysis, and some have even made

claims to same size and even bigger sizes than the two Theraphosa species.

The

majority of North American tarantulas are brown. Many species have more

extensive coloration patterns, ranging from cobalt blue (Haplopelma

lividum), black with white stripes (Eupalaestrus campestratus or Aphonopelma

seemanni), to metallic blue legs with vibrant orange abdomen (Chromatopelma

cyaneopubescens, green bottle blue). Their natural habitats include

savanna,

grasslands

such as the

pampas,

rainforests,

deserts,

scrubland,

mountains

and

cloud

forests. They are generally divided into terrestrial types that frequently

make burrows and arboreal types that build tented shelters well off the ground.

Sub-adult Female Poecilotheria regalis

The

eight legs, the two

chelicerae

with their fangs, and the

pedipalps

are attached to the prosoma. The chelicerae are two single segment appendages

that are located just below the eyes and directly forward of the mouth. The

chelicerae contain the venom glands that vent through the fangs. The fangs are

hollow extensions of the chelicerae that inject venom into prey or animals that

the tarantula bites in defense, and they are also used to masticate. These fangs

are articulated so that they can extend downward and outward in preparation to

bite or can fold back toward the chelicerae as a butchers knife blade folds back

into its handle. The chelicerae of tarantulas completely contain the venom

glands and the muscles that surround them and can cause the venom to be

forcefully injected into prey.

The

pedipalps are two six–segment appendages connected to the thorax near the

mouth and protruding on either side of both chelicerae. In most species of

tarantula, the pedipalps contain sharp jagged plates used to cut and crush food

often called the

coxae

or

maxillae.

As with other spiders, the terminal portion of the pedipalps of males function

as part of its reproductive system. Male spiders spin a silken platform (sperm

web) on the ground onto which they release semen from glands in their opistoma.

Then they insert their pedipalps into the semen, absorb the semen into the

pedipalps, and later insert the pedipalps (one at a time) into the reproductive

organ of the female, which is located in her abdomen. The terminal segments of

the pedipalps of male tarantulas are larger in circumference than those of a

female tarantula.

A

tarantula has 4 pairs of legs but 8 pairs of total appendages. Each leg has

seven segments which from the prosoma out are: coxa, trochanter, femur, patella,

tibia, tarsus and pretarsus, and claw. Two or three retractable claws are at the

end of each leg. These claws are used to grip surfaces for climbing. Also on the

end of each leg, surrounding the claws, is a group of hairs. These hairs, called

the scopula, help the tarantula to grip better when climbing surfaces like

glass. The fifth pair are the pedipalps which aid in feeling, gripping prey, and

mating for a mature male. The sixth pair of appendages are the fangs.

The

seventh and eighth pairs of appendages are the four spinnerettes, which also are

hypothesized by some to have been leglike appendages. When walking, a

tarantula's first and third leg on one side move at the same time as the second

and fourth legs on the other side of his body. The muscles in a tarantula's legs

cause the legs to bend at the joints, but to extend a leg, the tarantula

increases the pressure of blood entering the leg.

Tarantulas,

like almost all other spiders, have their spinnerets at the end of the

opisthosoma. Unlike spiders that on average have six, tarantulas have two or

four spinnerets. Spinnerets are flexible tubelike structures from which the

spider exudes its silk. The tip of each spinneret is called the spinning field.

Each spinning field is covered by as many as one hundred spinning tubes through

which silk is produced. This silk hardens on contact with the air to become a

thread like substance.

The

tarantula’s mouth is located under its chelicerae on the lower front part of

its prosoma. The mouth is a short straw-shaped opening which can only suck,

meaning that anything taken into it must be in liquid form. Prey with large

amounts of solid parts such as mice must be crushed and ground up or

predigested, which is accomplished by spraying the prey with digestive juices

that are excreted from openings in the chelicerae.

The

tarantula’s digestive organ (stomach) is a tube that runs the length of its

body. In the prosoma, this tube is wider and forms the sucking stomach. When the

sucking stomach's powerful muscles contract, the stomach is increased in

cross-section, creating a strong sucking action that permits the tarantula to

suck its liquified prey up through the mouth and into the intestines. Once the

liquified food enters the intestines, it is broken down into particles small

enough to pass through the intestine walls into the haemolymph (blood stream)

where it is distributed throughout the body.

Nervous system

A

tarantula's central nervous system (brain) is located in the bottom of the inner

prosoma. The central nervous system controls all of the body's activities. A

tarantula maintains awareness of its surroundings by using its sensory organs,

setae. Although it has eyes, a tarantula’s sense of touch is its keenest sense

and it often uses vibrations given off by its prey's movements to hunt. A

tarantula's setae are very sensitive organs and are used to sense chemical

signatures, vibration, wind direction and possibly even sound. Tarantulas are

also very responsive to the presence of certain chemicals such as pheromones.

The

eyes are located above the chelicerae on the forward part of the prosoma. They

are small and usually set in two rows of four. Most tarantulas are not able to

see much more than light, darkness, and motion. Arboreal tarantulas see better

than terrestrial tarantulas.

Respiratory system

In

all types of tarantulas there are two book lungs (breathing organs). The book

lungs are located in a cavity inside the lower front part of the abdomen near

where the abdomen connects to the cephalothorax. Air enters the cavity through a

tiny slit on each side of and near the front of the abdomen. Each lung consists

of 15 or more thin sheets of folded tissue arranged like the pages of a book.

These sheets of tissue are supplied by blood vessels. As air enters each lung,

oxygen is taken into the blood stream through the blood vessels in the lungs.

Needed moisture may also be absorbed from humid air by these organs.

A

tarantula’s blood is unique; an oxygen-transporting protein is present (the

copper-based

hemocyanin)

but not enclosed in blood cells like the erythrocytes of mammals. A

tarantula’s blood is not true blood but rather a liquid called haemolymph, or

hemolymphy. There are at least four types of hemocytes, or hemolymph cells. The

tarantula’s heart is a long slender tube that is located along the top of the

opisthosoma. The heart is neurogenic as opposed to myogenic, so nerve cells

instead of muscle cells initiate and coordinate the heart. The heart pumps

hemolymph to all parts of the body through open passages often referred to as

sinuses, and not through a circular system of blood vessels. If the exoskeleton

were to be breached, loss of hemolymph could kill the tarantula unless the wound

were small enough that the hemolymph could dry and close the wound.

Thermal image of a cold-blooded tarantula on a warm-blooded human

hand

Defense

Besides the normal "hairs" covering the body of tarantulas, some also have a dense covering of irritating hairs called urticating hairs, on the opisthosoma, that they sometimes use as a protection against enemies. These hairs are only present on New World species and are absent on specimens of the Old World.

These

fine hairs are barbed and designed to irritate. They can be lethal to small

animals such as rodents. Some people are extremely sensitive to these hairs, and

develop serious itching and rashes at the site. Exposure to urticating hairs

should be strictly avoided. Species with urticating hairs can kick off these

hairs: they are flicked into the air at a target using their back pairs of legs.

Tarantulas also use these hairs for other means; using them to mark territory or

to line the web or nest (the latter such practice may discourage

flies

from feeding on the spiderlings). Urticating hairs do not grow back, but are

replaced with each molt. The intensity, amount, and flotation of the hairs

depends on the species of Tarantula. Many owners of Goliath Bird Eating Spiders

(Theraphosa Blondi) claim that Theraphosa's have the worst urticating hairs.

To

predators and other kinds of enemies, these hairs can range from being lethal to

simply being a deterrent. With humans, they can cause irritation to eyes, nose,

and skin, and more dangerously, the lungs and airways, if inhaled. The symptoms

range from species to species, from person to person, from a burning itch to a

minor rash. In some cases, tarantula hairs have caused permanent damage to human

eyes.

Tarantula hair has been

used as the main ingredient in the novelty item "itching

powder", Some

tarantula enthusiasts have had to give up their spiders because of allergic

reactions to these hairs (skin rashes, problems with breathing, and swelling of

the affected area).

Some

setae are used to stridulate which makes a hissing sound. These hairs are

usually found on the chelicerae.

Stridulation

seems to be more common in

Despite

their often scary appearance and reputation, none of the true tarantulas are

known to have a

bite

which is deadly to humans. In general the effects of the bites of all kinds of

tarantulas are not well known. While the bites of many species are known to be

no worse than a wasp sting, accounts of bites by some species are reported to be

very painful. Because other proteins are included when a toxin is injected, some

individuals may suffer severe symptoms due to an allergic reaction rather than

to the venom. For both those reasons, and because any deep puncture wound can

become infected, care should be taken not to provoke any tarantula into biting.

Tarantulas are known to have highly individualistic responses. Some members of

species generally regarded as aggressive can be rather easy to get along with,

and sometimes a spider of a species generally regarded as docile can be

provoked. Anecdotal reports indicate that it is especially important not to

surprise a tarantula.

New

World tarantulas (those found in North and

Before

biting, tarantulas may signal their intention to attack by rearing up into a

"threat posture", which may involve raising their prosoma and lifting

their front legs into the air, spreading and extending their fangs, and (in

certain species) making a loud hissing noise called Stridulating. Their next

step, short of biting, may be to slap down on the intruder with their raised

front legs. If that response fails to deter the attacker they may next turn away

and flick urticating hairs toward the pursuing predator. Their next response may

be to leave the scene entirely, but, especially if there is no line of retreat,

their next (or first) response may also be to whirl suddenly and bite.

Tarantulas can be very deceptive in regard to their speed because they

habitually move very slowly, but are able to deliver an alarmingly rapid bite

when sufficiently motivated.

There

are, however, dangerous spiders which are not true tarantulas but which are

frequently confused with them. It is a popular

urban

legend that there exist deadly varieties of tarantulas somewhere in

Encourage

bleeding to wash out the puncture wounds from within, then clean the bite site

with soap and water and protect it against infection. As with other puncture

wounds, antiseptics may be of limited use since they may not penetrate to the

full depth of a septic wound, so wounds should be monitored for heat, redness,

or other signs of infection. Skin exposures to the urticating hairs can be

treated by applying and then pulling off some sticky tape such as duct tape,

which carries the hairs off with it.

If

any breathing difficulty or chest pain occurs, go to a hospital as this may

indicate an

anaphylactic

reaction. As with bee stings, the allergic reaction may be many times more

dangerous than the toxic effects of the venom. If this occurs an

EpiPen

(an autoinjector of epinephrine, also known as adrenaline) should be

administered as soon as possible, as complete airway blockage can occur within

20 minutes of exposure to the allergen.

Sexual dimorphism

Some

tarantula species exhibit pronounced

sexual

dimorphism. Males tend to be smaller (especially the abdomen, which can

appear quite narrow) and may be quite dull when compared to their female counter

parts, as in the species Haplopelma lividum. Mature male tarantulas also have

tibial hooks on their front legs, which are used to restrain the female's fangs

during copulation.

A

juvenile male's sex can be determined by looking at a cast exuvium for

exiandrous fusillae or spermathecae. Ventral sexing is less reliable but if done

correctly, it can be relatively reliable. Males have much shorter lifespans than

females because they die relatively soon after maturing. Few live long enough

for a post-ultimate molt. It is unlikely that it happens much in natural habitat

because they are vulnerable, but it has happened in captivity rarely. Most males

do not live through this molt as they tend to get their emboli, mature male

sexual organs on pedipalps, stuck in the molt. Most tarantulas kept as pets are

desired to be female. Wild caught tarantulas are often mature males because they

wander out in the open and are more likely to be caught while females remain in

burrows. A stressed tarantula huddles up in the corner with its legs tucked

close to it, does not react, or reacts slowly to touch. A dying tarantula will

curl its legs like a clutched hand under it. Its movement is hydraulically

motivated and an extended leg takes more energy than a curled one. Tarantulas do

not die on their backs unless there is trouble molting.

Excessive

dryness can kill tarantulas, especially tropical tarantulas. Although higher

humidity helps with molting, it appears that for many tarantulas, humidity does

not highly affect molting as much as the actual hydration of the tarantula prior

to molting. Most notably though, Theraphosa species must be high in humidity to

molt.

The molting process

Like

other spiders, tarantulas have to shed their

exoskeleton

periodically in order to grow, a process called

molting.

Young tarantulas may do this several times a year as a part of their maturation

process, while full grown specimens will only molt once every year or so, or

sooner in order to replace lost limbs or lost urticating hairs. A tarantula is

obviously going to molt (or "shed, as some call it) when the exoskeleton

takes on a darker shade. If a tarantula previously used its urticating hairs,

the bald patch will turn from a peach color to deep blue.

Tarantulas

may live for years--most species taking 2 to 5 years to reach adulthood, but

some species may take up to 10 years to reach full maturity. Upon reaching

adulthood, males typically have but a 1 to 1.5 year period left to live and will

immediately go in search of a female with which to mate. It is rare that upon

reaching adulthood the male tarantula will molt again. The oldest spider,

according to

Guinness

World Records, lived to be 49 years old

Females

will continue to molt after reaching maturity. Female specimens have been known

to reach 30 to 40 years of age, and have survived on water alone for up to 2.5

years. Grammostola rosea spiders are renowned for going for long periods without

eating.

Reproduction

As

with other spiders, the mechanics of intercourse are quite different from those

of mammals. Once a male spider reaches maturity and becomes motivated to mate,

it will weave a web mat on a flat surface. The spider will then rub its abdomen

on the surface of this mat and in so doing release a quantity of semen. It may

then insert its pedipalps (short leg-like appendages between the chelicerae and

front legs) into the pool of semen. The pedipalps absorb the semen and keep it

viable until a mate can be found. When a male spider detects the presence of a

female, the two exchange signals to establish that they are of the same species.

These signals may also lull the female into a receptive state. If the female is

receptive then the male approaches her and inserts his pedipalps into an opening

in the lower surface of her abdomen, called the Opithosoma. After the semen has

been transferred to the receptive female's body, the male will swiftly leave the

scene before the female recovers her appetite. Although females may show some

aggression after mating, the male rarely becomes a meal.

Females

deposit 50 to 2000 eggs, depending on the species, in a silken egg sac and guard

it for 6 to 7 weeks. During this time, the female will stay very close to the

eggsac and become more aggressive. The female turns the eggsac often, which is

called brooding. This keeps the eggs from deforming due to sitting too long. The

young spiderlings remain in the nest for some time after hatching where they

live off the remains of their yolk sac before dispersing.

Tarantulas

as Pets

|

adult

Mexican Redknee |

Chilean

Rosehair |

Tarantulas

can be kept as

pets

and are considered good "apartment pets" by many, being quiet animals,

requiring surprisingly little maintenance or cleaning, since unlike

snakes

and

lizards

they have no detectable odor. Because of their docile behavior, the species most

commonly kept as pets are the

Chilean

rosehair tarantula (Grammostola rosea), for their price and the

Mexican

redknee tarantula (Brachypelma smithi), for their beauty. These two species

are also some of the easier to care for and are usually easy to handle, while

other species (Including most Asian species, such as the

cobalt

blue tarantula) are more aggressive and shouldn't be handled. Some of the

more docile types seem to have a habit of relaxing in people's hands, perhaps

attracted by the warmth.

Tarantulas

make quite inexpensive pets. Most species can be purchased as juveniles for

$20-$50 USD. Adults can be quite expensive as they approach breeding age, and

adults of many species can easily reach the several hundred US dollar range.

Housing for most species can cost another 40 USD.

A

terrarium

with an inch or two of damp ground coconut fiber, or a mixture of soil and

sphagnum

moss (but not with cedar shavings as they are toxic to many spiders) on

bottom provides an ideal habitat. (Burrowing tarantulas will require a much

deeper layer.) Harder substances such as gravel and sand are not suitable for a

thriving tarantula; If a tarantula falls too far into a hard surface it can

easily injure itself. Sand doesn't hold moisture well and tarantulas are

generally prone to dehydration. Ambient temperature and humidity vary by

species, with most thriving between 75 degrees and 80°F

(24 to 27°C)

and between 40% and 80% humidity.

Tarantulas can be fed living animals such as insects, small mice or Pinky Mice, and small fish in the water bowl. A tropical roach colony is a good way to maintain a food supply for a number of tarantulas. The discoid cockroach and death's head cockroach in particular are very easy to care for and will not infest the home if they escape. The death's head cockroaches can be kept in an aquarium with no lid since they cannot climb glass and don't fly. Maintaining a colony of death's head cockroaches only requires keeping them in the dark, feeding them a handful of dog food every couple of weeks and misting them with water every day or two.

Other

tarantulas that may make interesting pets are the

Brazilian

whiteknee tarantula,

Chaco

golden knee, and

Brazilian

salmon pink birdeater. These are three of the larger species, each growing

over 8 inches with the Brazilian birdeater sometimes reaching 10 inches and

considered by many to be the largest species that is docile enough to handle.

The foregoing are terrestrial tarantulas, i.e., they generally live in burrows

or natural shelters near the ground. Arboreal tarantulas require different

housing since, when adult, they make webbed shelters well above ground. Those

include Avicularia avicularia and Avicularia metallica, which are generally

quite calm and rarely bite. (Any spider will bite if it is being hurt or put in

fear for its life.) The arboreal spiders can have large legspans, but their

bodies are much less massive than the typical terrestrial tarantulas.

Avicularia

metallica, immature female

The

Goliath

birdeater tarantula (Theraphosa Blondi) is considered a delicacy by the

indigenous

Piaroa

of

Venezuela.

Another appearance of the tarantula as food was made on

Anthony

Bourdain's

A

Cook's Tour.

Fried

tarantulas are also considered a delicacy in

Cambodia.

Etymology

The

word tarantula applies to several very different kinds of

spider.

The spider originally bearing that name is one of the

wolf

spiders,

Lycosa

tarantula, found in the region surrounding the city of

Taranto

(or Tarentum in Latin), a town in Southern

Italy.

Compared to true tarantulas, wolf spiders are not particularly large or hairy.

The

bite of L. tarantula was once believed to cause a fatal condition called

tarantism,

whose cure was believed to involve wild dancing of a kind that has come to be

identified with the

tarantella.

However, modern research has shown that the bite of L. tarantula is not

dangerous to human beings. There appears to have existed a different species of

spider in the fields around

When

theraphosidae were encountered by European explorers in

the

Americas, they were named "tarantulas". Nevertheless, these

spiders belong to the suborder

Mygalomorphae,

and are not at all closely related to wolf spiders.

The

name "tarantula" is also applied to other large-bodied spiders,

including the purseweb spiders or

atypical

tarantulas, the funnel-web tarantulas (Dipluridae

and

Hexathelidae),

and the

dwarf

tarantulas. These spiders are related to true tarantulas (all being

mygalomorphs), but are classified in different

families.

Huntsman

spiders of the family

Sparassidae

are also informally referred to as "tarantulas" because of their large

size. They are not related, belonging to the suborder

Araneomorphae.