PHYLUM ECHINODERMATA

Echinoderms include common seashore animals such as seastars (also known as

"starfish"), sand dollars and sea urchins, along

with hundreds of more exotic forms. Their basic body plan is very different from

other animals, but their closest living relatives

are the Phylum Chordata (which includes the vertebrates). Although they are marine animals, they are not closely related to the

Cnidarians due to the fact that Cnidarians DO NOT have endoskeletons.

Echinoderms are exclusively marine, and most are benthic. They are present in

virtually all marine environments of normal

salinity, from the shallow intertidal to the abyssal zone. Many echinoderms are

suspension feeders, while others are predators,

scavengers and herbivores. A few are deposit feeders.

Although the phylum is quite diverse, echinoderm physiology and their body plan

display a surprising uniformity. They are

characterized by an internal skeleton (endoskeleton) composed of calcitic plates

(ossicles), and a water vascular system. The

ossicles have a porous microstructure that is distinctive. A major feature of

the skeleton is that the ossicles may increase in size

during the growth of the animal. This feature is what scientists use as their basis for classifying them closely with the chordates.

The main portion of the body skeleton, known as the theca or calyx in most

echinoderms, may have accessory appendages

(arms, rays, stem or brachioles).

The water vascular system is an interesting system unknown in any other phylum.

In ancient echinoderms, water circulated

through pores in the body wall and was apparently important for respiration and

feeding. More derived taxa have a specialized

system where the water is drawn through a sieve plate (madreporite) by the

action of cilia or internal pumping. The water enters

a calcified tube and is directed to various parts of the animal. The water

eventually fills small sacs inside external tube-like

extensions (the tube feet or podia) along the rays and these, through hydraulic

manipulation, may pulsate to move the animal

through the environment or transport food to the mouth.

Echinoderms are generally radially symmetric, with adults displaying a secondary

pentaradial symmetry. The symmetry is

secondary, because echinoderm larvae are bilaterally symmetric. One group, the

sea cucumbers, develop a tertiary bilateral

symmetry. The mouth is located centrally on the lower surface of the animal (oral surface). The other surface is termed the aboral surface.

A coiled gut extends from the

mouth to an anus, which is situated between two

rays or at the posterior end. Echinoderms have a well-developed nervous system

and reproductive system, but no heart (no

need with the water vascular system).

Phylum Echinodermata contains over a dozen classes, about half of which are

known only from the Paleozoic. They are

classified by characters such as the general morphology, ossicle structure,

arrangement of the water vascular system, and

embryology.

The homalozoans include the "carpoid" echinoderms and possibly another minor

group. Carpoids are small and rare fossils

found only in Lower and Middle Paleozoic rocks. They have an asymmetric,

flattened body composed of calcitic plates, and a

short stem called an aulacophore. Carpoids have been assigned to the

Echinodermata because the calcite of their plates has a

characteristic echinoderm microstructure, and because most bear a food groove of

some type.

Pelmatzoans are ehinoderms that are radially symmetrical to some degree, have a

generally cupshaped body (theca) enclosing

the viscera, and possess food-gathering appendages (arms or brachioles)

extending from the theca. Most pelamtozoans have a

jointed stem that is usually used to attach the animal to the substrate.

Only this group of pelmatozoans is not confined to the Paleozoic. Crinoids are

the most diversified and common

members of the subphylum-in some Paleozoic deposits their scattered ossicles

form the bulk of the rock. The typical

crinoid has a long stem with "roots" or some other attachment device (holdfast)

at the lower end, and a cup-shaped

thecum at the top. Several arms extend from the dorsal surface of the theca to

collect suspended food. These arms are

commonly branched and bear calcitic columnals very similar to those of blastoids

and cystoids. Some crinoids have lost

the stem and become mobile. Recent crinoids are found mostly at bathyal depths,

though some are common in tropical

reef and shallow cave habitats. They range from polar to tropical latitudes. The

Paleozoic forms were very common on

shallow carbonate platforms. Four subclasses were recognized, only one of which

(the Articulata) is extant today.

This ancient group is widely distributed in Early and Middle Paleozoic rocks.

The cystoid theca is usually globular or

saclike, with radial or, rarely, bilateral symmetry. It is made of numerous

plates, regularly or irregularly arranged, that are

pierced by a characteristic pore system. The stem, or column, is made of

numerous circular or elliptical plates, known as

columnals. Not all cystoids had a column, and many apparently did not use it for

attachment. The feeding system of a

cystoid consisted of a set of brachioles, which were free appendages on the

dorsal surface used for gathering suspended

material. The class is divided into two main groups based on the structure of

the thecal pores.

The blastoids were stemmed forms with pronounced pentaradial symmetry and a very

regular distribution of thecal

plates. The theca is the most commonly preserved part of the animal- it has the

general shape and approximate size of a

rosebud. The majority of blastoids have 13 thecal plates arranged in three

circlets. The ambulacral areas are specialized

and bear numerous food-gathering brachioles. All blastoids have a distinctive

structure called the hydrospire that hangs

into the body cavity beneath each ambulacrum; it is thought to have functioned

as a respiratory device.

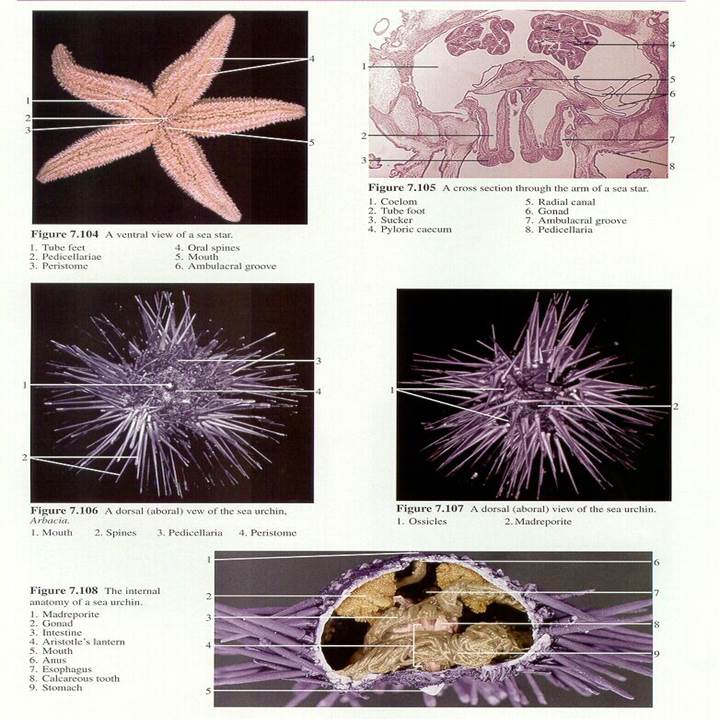

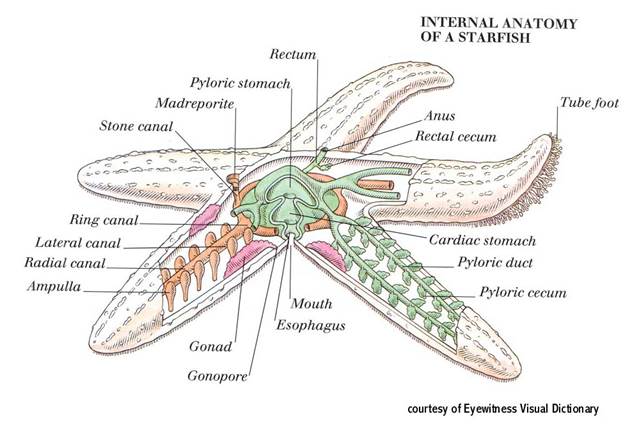

These are the typcial seastars found along the seashore. They generally have

hollow arms, into which the coelomic cavity

exends; the radial canals are located on the outside of the skeleton. Asteroids

crawl by concerted actions of their podia,

and so are very sluggish movers. Most are carnivorous, feeding on all types of

benthic animals. Clams are the most

common food - some species can force the valves apart and extrude their stomachs

into the shell to digest the meat.

Gastropods and cnidarians are other favourite items. The lower side of each arm

contains an ambulacral groove with

open radial water vessels and numerous large podia.

In contrast to the asteroids, the ophiuroids are active crawlers with whip-like

arms that wriggle like snakes (hence they

are sometimes called serpent stars). They have a robust central disc that

contains all the viscera. The arms are not

hollow, but are filled with a series of articulating ossicles resembling the

vertebrate backbone. Ophiuroids are also called

brittle stars because of their habit of releasing arms at ossicle sutures to

escape predation or other antagonistic

behaviours. This process of releasing a limb is called autotomy. The lost limb

is eventually regenerated.

Many ophiuroids are deposit feeders, while some capture suspended food or small

prey with their podia (suspension

feeding). The mouth is centrally located on the lower side and leads to a blind

gut with no anus.

These

echinoderms are found throughout the Paleozoic, although they are usually rare.

They have a saclike to discoidal

theca made of

many irregular plates. Usually five straight or curved ambulacral areas extend

from the mouth, which is

located

centrally on the upper surface. Most edrioasteroids attached themselves to some

firm object, such as a shell or

rock. This

extinct class now includes cyclocystoids.

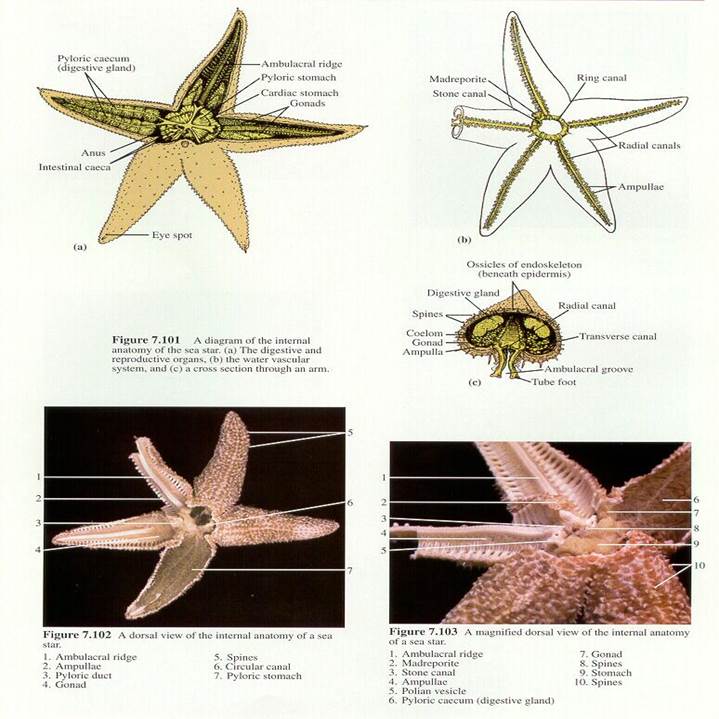

This group includes the sea urchins (regular echinoids), heart urchins (spatangoids),

and sand dollars (clypeasteroids).

Echinoids are usually globular, discoidal or heart-shaped and have a skeleton

made of many calcitic plates. The skeleton

has five ambulacral areas, each numerously perforated for the tube feet, and

five interambulacral areas, which bear

spines. Echinoids have a unique jaw apparatus known as Aristotle's Lantern that

is protrusible from the mouth. The most

ancient echinoids have the anus (with its set of enclosing plates, the periproct)

located in the center of the aboral surface

(the "regular" condition). Some later forms show a gradual migration of the

periproct toward the border (the "irregulax"

condition).

Regular echinoids can be distinguished easily from irregular echinoids by their

circular test, nearly perfect pentameral

symmetry, and the central location of the anus (directly above the mouth). The

ambulacra have 2 or more columns of

plates. The interambulacra have one or more columns of plates and are all

similar. The spines are generally long and an

Aristotle's lantern occurs in all taxa. All Paleozoic echinoids were regular.

Irregular echinoids are distinctively elongate in the adult stage. This shape

difference as well as the posterior position of

the anus (instead of dorsally, like the regular echinoids) are the 2 most

telltale differences setting the two types apart.

Irregulars also usually have petals on the upper surface, and each ambulacrum

and interambulacrum has 2 columns of

plates (with the exception of the posterior ambulacrum, which differs from the

others). Spines are generally short and

Aristotle's lantern is absent in most adult forms, except for the sand dollars.

The irregulars underwent a spectacular

radiation in the Mesozoic and are much more common as fossils, compared to the

regulars. The derived irregulars also

have concentrated the respiratory devices on the aboral surface, and have

developed food grooves.

These are the sea cucumbers, which do not superficially resemble any of the

other echinoderms. Close examination however

reveals that they do have a pentaradial symmetry, but the anus is opposite the

mouth on an elongated oral-aboral axis. The

calcitic plates are reduced to dermal, microscopic sclerites, which are often

used in classification schemes. They have a water

vascular system and podia. Holothurians are generally deposit feeders- they use

small tentacles surrounding the mouth for

particle collection. Several species are suspension feeders. A few rare forms

are planktonic.