Ecology of Prey/Predator Relationships

The predator prey relationship consists of the interactions between two species and their consequent effects on each other. In the predator prey relationship, one species is feeding on the other species. The prey species is the animal being fed on, and the predator is the animal being fed. The predator prey relationship develops over time as many generations of each species interact. In doing so, they affect the success and survival of each other’s species. The process of evolution selects for adaptations which increase the fitness of each population. Scientists studying population dynamics, or changes in populations over time, have noticed that predator prey relationships greatly affect the populations of each species, and that because of the predator prey relationship, these population fluctuations are linked.

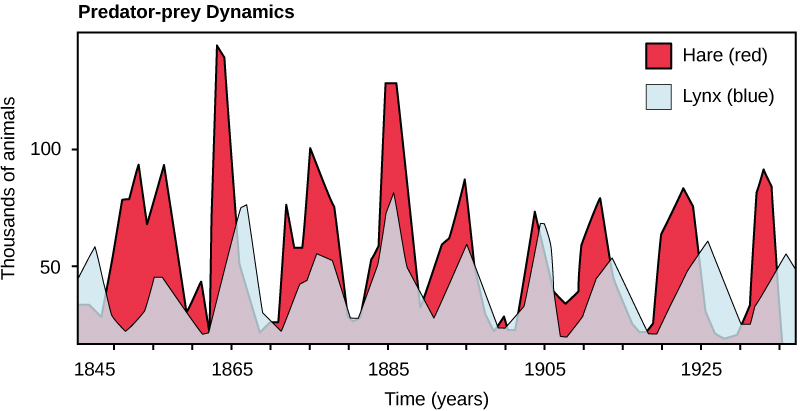

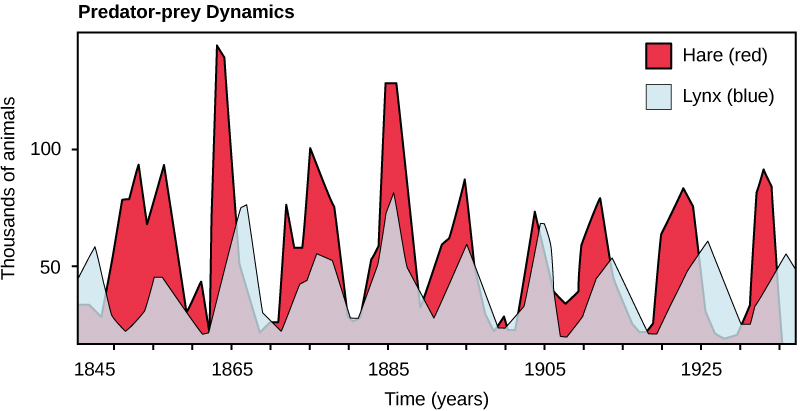

In some predator prey relationship examples, the predator really only has one prey item. In these scenarios, it is easy to see how the predator prey relationship affects the population dynamics of each species. A simple example is the predator prey relationship between the lynx and the snowshoe hare. The hare forms a large staple in the lynx diet. Without the hare, the lynx would starve. However, as the lynx eats the hare, or many hares, it can reproduce. Thus, the lynx population expands. With more lynx hunting, the hare population rapidly declines. Look at the graph below.

The blue shows the population of lynx, while the red shows the population of hares. At the start of the graph, the lynx population was very high, which the hare population was relatively low. As the lynx started to migrate away, or die off, the hare population rebounded. Since 1845, this 10 year pattern has continued to repeat itself, with a lynx die off coming right after the hare die off. The predator prey relationship between the hare and the lynx helps drive this pattern. However, if you average out the peaks of the population, both populations would hold stable or show only a slight increase or decrease over time.

Remember also that the hare also has a predator prey relationship with the organisms it feeds on, which happen to be plants. As the hares explode, they eat more than the vegetation can support, and they are driven into starvation. That, plus their predator prey relationship with the lynx, makes for very volatile shifts in population.

As these populations continue to reproduce over time, the actions of natural selection can also change the species to make them better predators, or more defensive prey. Either way, this adaptation changes the entire predator prey dynamic. If one species cannot then adapt an appropriate defense, they may go extinct. In this way, the predator prey relationship often forms an “evolutionary arms race”, in which eat species rapidly evolves to counter the other.

While numerous examples have been observed of the evolution of traits via the predator prey relationship, some of the most interesting examples occur when the relationship is suspended. In tests on guppies, scientist have shown that a large, colorful spot is a sexually selected trait. Male guppies with brightly colored spots are preferred by females. However, predators can easily spot these colors, and eat the brightest colored males.

In streams where predators are not present, the males become brightly colored with dark spots (as seen below). Sexual selection rapidly evolves the males to be brightly colored, and their novelty and brightness drive their evolutionary success. Sexual selection is a mechanism of evolution that occurs when some individuals have a reproductive advantage over others of the same species due to their success in competing for mates.

In streams with predators, the males that succeed do so not necessarily because they were the most attractive with the brightest spots, in fact, they have very few brightly colored spots if any (as shown below). Instead, they are successful because they lived longer, in part because they did not have the brightly colored spots. The predator prey relationship in this case overpowered the pressure of sexual selection. It is a good example of how the predator prey relationship can greatly influence the path of evolution.

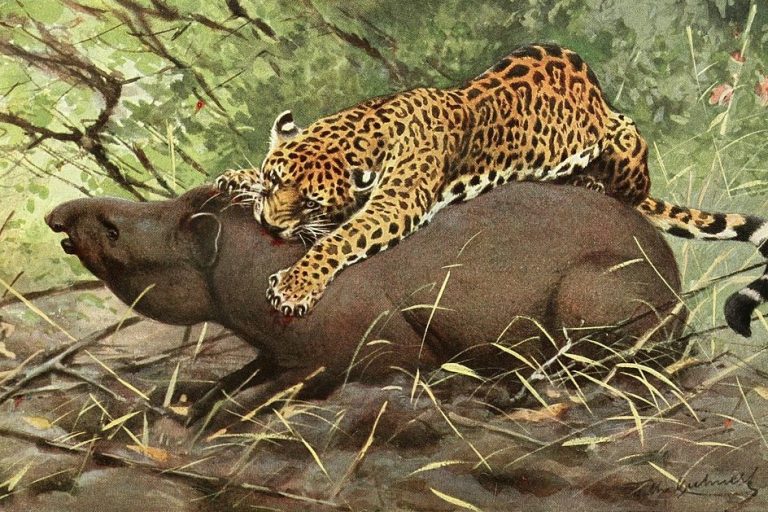

Typically, a species has more than one predator prey relationship. Consider a jaguar for example. The jaguar is a solitary predator. Solitary predators prefer to hunt and live alone. Other solitary predators include the leopard, polar bears, hawks, eagles, tigers, snow leopards, etc.

The jaguar is a predator of many different animals, from wild hogs to caiman. With each of these species, it maintains a predator prey relationship. However, the jaguar is also a prey item for certain species. Baby jaguars stay with their mothers for a year or more before being able to fully protect themselves. Anacondas, large birds, and other felines are just some of the perils in store for a young jaguar.

|

|

|

|

|

The jaguar represents what is known as a conventional predator. A conventional predator hunts, kills, and eats other organisms. While jaguars are solitary predators, there are also social predators. Social predators are organisms that hunt in groups. By hunting in groups, they are more successful than solitary predators, however, they need to make more kills to feed the entire group. Social predators include species like wolves, orcas, dolphins and lions. The differences in these social structures represent the different evolutionary niches that the species have carved out, as well as the past predator prey relationships which shaped the animals as they are today.

|

Besides the conventional predators, many organisms fit the definition of predator outside of the typical boundaries. Scavengers, as a type of predator, have a predator prey relationship with each of the species that they feed on. Vultures and hyenas are some of the most well known scavengers within an ecosystem. A scavenger is is an organism that primarily feeds on dead or decaying organic matter, like the remains of animals killed by other predators or those that died naturally, essentially cleaning up the environment by consuming carrion (dead animal flesh) and sometimes decaying plant material; they typically do not actively hunt their own prey. For instance, a scavenger like a vulture is affected when the population of water buffalo falls. With less buffalo, the lions die off and make less kills, and then the vulture itself is affected. While this may be a lopsided predator prey relationship because the vulture doesn’t directly kill the buffalo, it is still affected by the population of buffalo. In this case, the nonconventional predator (vulture) is dependent on the conventional predator (lion) for food. Luckily for vultures, they scavenge many species and aren’t reliant only on the buffalo population. This is not true for all scavengers.

Other nonconventional predators include parasites, which feed off of a host organism, but do not necessarily kill it. While the predator may be much smaller than the prey, they still have a relationship. The predator prey relationship between deer and ticks, for example, is very similar to the predator prey relationship between the lynx and hare. As the deer die off, the ticks have less to feed on, especially ticks which specialize on deer. The decline is caused in part by the ticks themselves, which add a parasitic load to the deer, and transfer disease within the population. The ticks will then reduce in numbers, allowing the deer to flourish. So in reality, the large population of ticks will lead to their own demise over a period of time. Other parasitic organisms would include tapeworms, liver flukes, lice, and hookworms.

Almost 10% of all known insects show a special form of parasitism. These parasitoids, as they are known, have developed a special predator prey relationship in which they lay their eggs on or inside the body of another species. The larva hatch, and eat their way out as the host slowly dies. While the adult is not consuming the other species directly, the larvae do. Below is a picture of a parasitoid wasp called the tarantula hawk wasp, dragging a tarantula it has paralyzed with its sting. The wasp will now be able to lay eggs in the living tarantula, which will hatch and devour the spider from the inside.

Plants are often overlooked as both prey and predators because they seem indifferent to the actions around them. However, many experiments and observations have shown that plants are active participants in the relationship. A stunning example is that of plant communication in response to predators. It has been shown that certain species of plants have evolved a specific defense to overgrazing. After moderate grazing levels have been surpassed, and the plant is in danger, it will begin releasing the hormone gas ethylene into the air. Other plants receive this hormone signal, and begin producing toxic substances in their leaves. Animals which feed on these plants become sick and die. In this way, an evolutionary battle and predator prey relationship has been evolving between plants and herbivores since they first coexisted.

Further, plants can be direct predators, and evolve complex predator prey relationship characteristics from that side as well. Consider the Venus Fly Trap, pictured below. This plant has developed directly as a predator of many flying insects. The plant not only has special hairs on the leaves which can sense the motion of insects and large spines to entrap them, but they also actively secrete substances to attract the insects. Other plants have developed different forms of insect traps, and they provide the plants with extra nutrients. This predator prey relationship is not much different than a snake waiting for a mouse to cross its path.

Prey/Predator Relationships Among Coral Reefs

Eat or Be Eaten: Predators and Prey, Parasites and Hosts

Actually, it's more like eat and be eaten for most organisms. While plants and some bacteria can make their own food, other organisms must eat living things to survive. This makes them predators. You might not think of a grass-munching cow as much of a predator, but cows are indeed the predators of their grass prey.

Of course, the cows themselves are prey to other animals, like humans and coyotes. Now we have a simple food chain, with grass plants making food at the bottom, cows as middle predators, and then humans and coyotes as "top predators."

While predators usually kill their prey to eat them, parasites live on or in their prey (called a host), nibbling or sucking tiny bits so the host survives, nourishing them for many meals to come. Almost all organisms play host to parasites throughout their entire lifetimes.

To succeed at the evolutionary game, organisms must eat but not be eaten. As a result, in predator-prey (and parasite-host) relationships, something called coevolution can often occur. Coevolution is the process by which two or more species evolve in response to each other's interactions. This often occurs as one of them develops a new offense or defense, the other must develop a counter-weapon in order to survive.

Here are some different prey/predator relationships on the coral reef:

Giant Triton (snail) > Crown of Thorns Starfish > Hard Coral

One of the few predators of the crown-of-thorns starfish, the giant triton (Charonia tritonis) has evolved a tolerance to the starfish's toxins. Unfortunately, tritons can no longer keep starfish populations in check since they've been overharvested for their beautiful shells. With too few tritons on the reef, crown-of-thorns starfish populations can explode, jeopardizing the living coral that makes up reefs.

Covered with long, venomous spikes, the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) is a voracious feeder that can eat living corals because of a unique adaptation: a wax-digesting enzyme system. Populations of the starfish were once kept low by a few key predators, namely the giant triton. Since humans decimated giant triton populations, crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks periodically kill vast expanses of hard coral.

Hard corals have evolved to have large amounts of a wax (cetyl palmitate) in their tissues. Very few predators can digest the wax, which has allowed corals to flourish and produce massive reefs. Recently, epidemic populations of one predator -- the crown-of-thorns starfish -- have done extensive damage to many reef regions. Armies of grazing starfish leave a wake of destruction in their path, killing up to 95 percent of the hard corals in an area.

Tiger Shark > Green Sea Turtle

Lurking around the edges of reefs during the day, tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) have evolved as highly aggressive "top" predators that grow at least 25 feet long. They detect prey using an array of finely tuned senses, including electrical current detection. Rows of razor-sharp teeth and powerful jaws allow them to crack though even the thick carapace (shell) of full-grown sea turtles.

One common defense against predators is a protective covering, such as a shell. Another is to flee the predator. During its evolution, the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) sacrificed speed in favor of a thick, heavy shell (carapace). The carapace acts as armor, protecting the turtle's body from the sharp teeth of predators. But some, like the tiger shark, are powerful enough to bite right through the carapace and kill the turtle.

Sea Slug > Sea Sponge

Many sea sponges, like anemones, use toxins to repel would-be predators. Some species of sea slugs, however, such as Platydoris scabra, have evolved immunity against the toxins of specific sponge families (in this case, Microcionidae). This adaptation benefits the slugs in two ways. First, they don't have to compete with many other organisms for the sponges. The sea slugs can also concentrate the sponge toxins to foil their own predators -- at least until the slugs' predators also evolve immunity to the toxins.

Sea sponges, such as those of the Microcionidae family, have escaped predation by all but a few species because they produce foul-tasting and sometimes toxic compounds. These compounds evolved as chemical weapons for use against other sponges, as well as against fouling organisms (creatures that grow on top of other creatures, thus decreasing their fitness) -- their defensive function was just a lucky side effect. But some predators, such as sea slugs, have evolved resistance to the toxins and even use those toxins against their own predators.

Barracuda > Parrot Fish > Benthic Algae

Barracuda (Sphyraena spp.) are fierce predatory fish that patrol outer reef areas in large schools. Like many predators, they have evolved as extremely fast swimmers, with streamlined, torpedo-like bodies. And they are efficient killers, using conical, razor-sharp teeth to quickly rip prey to shreds. In addition, they are resistant to the toxin found in the bodies of many of their prey, such as parrotfish.

Named for their bright colors and beak-like mouths, parrotfish (Scaridae family.) are large herbivores that graze on the algae growing atop hard corals. Using their beaks and two pairs of crushing jaws, parrotfish are marvelously adapted for crunching and pulverizing chunks of algae-coated coral. They digest the algae and excrete the coral as fine sand. Unfortunately, they are poorly equipped to defend themselves against predators, such as barracuda, but some find protection by schooling with better-armored fish.

Algae occur in a kaleidoscope of forms and colors on the reef, but they have one main function: turning solar energy into food. Thus they are called "primary producers." Without them, the reef would quickly become a lifeless moonscape. One important algal group, benthic (bottom-dwelling) algae, rapidly grows over dead coral and other inert objects, providing a grazing yard for herbivores, such as parrotfish.

Saddled butterflyfish > Sea Anenome

Saddled butterflyfish (Chaetodon ephippium) seem to flutter, rather than swim, above the algae-covered coral they commonly graze on. Their gentle disposition disappears, however, in the presence of another favorite food: sea anemones. When feeding, the butterflyfish turn into vicious predators, darting in to rip off the anemones' fleshy tentacles. Having evolved resistance to the anemones' toxins, they need only get past clownfish guards to pick off a delicious meal.

Packed with miniature toxin-loaded harpoons (nematocysts), the tentacles of sea anemones provide an excellent deterrent against almost all would-be predators. Saddled butterflyfish, though, have evolved resistance to the toxins and apparently relish the tentacles. Still, to grab a meal, the butterflyfish must get past the anemones' second line of defense: zealous clownfish guards.

Smallscale Scorpionfish > Goby (fish)

Just as some prey species have evolved cryptic coloration and patterns that help them avoid predation, some predators have evolved camouflage that lets them hide themselves and ambush their prey. One such predator, the smallscale scorpionfish (Scorpaenopsis oxycephala), closely resembles the reef's rocky, algae- and coral-encrusted bottom, where it lies in wait for crustaceans and small fish, such as gobies.

Safely tucked in coral crevices or half-buried in sand and rubble, gobies (Gobiidae family) maintain a low profile on the reef to avoid predation. In addition, they have evolved independently swiveling eyes that constantly search the water for potential attackers. But their efforts can be foiled by ambush predators, like the smallscale scorpionfish, whose camouflage prevents gobies and other prey from seeing them until it's too late.

Bluestriped Fangblenny (fish) > Reef Lizardfish

Many large fish, including the reef lizardfish (Synodus variegatus), regularly visit the bluestreak cleaner wrasse to have skin, mouth, and gill parasites removed. The two fish benefit by the association; a third fish, however, has evolved to take advantage of them both. Using a devious disguise and copycat behaviors to attract larger fish, the fanged ambush predator, called a fangblenny, rips living tissue from surprised prey.

In the world of predators and prey, the normal rule is that big creatures eat smaller creatures. But sometimes the tables are turned, as in the case of the bluestriped fangblenny (Plagiotremus rhinorhyncos), a small but sinister predatory fish. Evolved to perfectly mimic the bluestreak cleaner wrasse, the fangblenny falsely advertises cleaning services to larger fish, such as the reef lizardfish. Once the bigger fish moves in close, the fangblenny attacks and darts away with a mouthful of sushi.

Coneshell (snail) > Blueband Goby (fish)

Coneshells (Conus spp.) are gastropod mollusks, closely related to the more familiar and harmless land snails. With beautiful, ornately designed shells, coneshells are highly sought-after by shell collectors. These gastropods have evolved as deadly predators, however; a single puncture from their venomous radula (modified tooth) can rapidly paralyze and even kill a human. Of course, coneshells evolved not to defend themselves against collectors, but to efficiently kill prey, such as the blueband goby.

Gobies are the most diverse fish family on the reef, with more than 200 species described. With their generally small sizes and ability to adapt to a wide variety of specialized habitats, gobies have become the most diverse marine fish family in the world. This does not mean they are always successful at avoiding predators, though. For instance, the blueband goby (Valenciennia strigata) is eaten by a variety of predators, including the venomous coneshell.

Silver gull > Black Noddy

Coming ashore only to breed (as do most true seabirds), black noddies (Anous minutus) form immense colonies of up to 100,000 nesting pairs on larger reef islands. Noisily chattering as they work, mating pairs build nests of guano-cemented leaves and grasses in fig trees. But even in the shelter of the trees, chicks and eggs are often stolen and eaten by marauding silver gulls.

The common silver gull (Larus novaehollandiae), like most gulls, will eat just about anything it can get its heavy, hooked bill into. Often scavenging recently dead animals and even trash, silver gulls help keep shore areas clear of debris. But once the debris is gone, they turn to other easy pickings: eggs and chicks of other seabirds, such as the black noddy.

Reef heron > Fish Fry

Reef herons (Egretta sacra), unlike true seabirds, live onshore year-round. While seabirds hunt far out beyond the reef, reef herons fish along the cay and reef flat. They have evolved to hunt during low tide, allowing them to wade the shallows. With excellent eyesight and marksman-like aim, they expertly spear fish fry, adult fish, and crustacean prey from beneath the water's surface.

Silvery schools of many species of juvenile fish (called fish fry) find some refuge from the intense predation of outer reef zones by living near the shoreline. But they can't let down their guard completely. While feeding on benthic algae and floating microscopic communities of plants and animals, they are easily visible from above the water's surface and often fall prey to hunting reef herons.